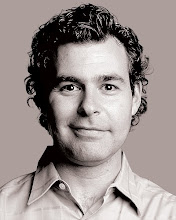

That, above, is by a large margin my most cherished photo from any story I ever did. Not because I am much of a pro basketball fan or even paid much mind of Yao Ming's career while he played in the NBA, but just because of the bizarre dimensions of the thing and how he grumpy he looks. No, I did not step on his toe.

With Yao announcing in Shanghai the

end of his NBA career this week, it seems worthwhile and fun for me to go reminisce on my involvement in its start. That picture was shot on an early April 2001 afternoon in a hotel room in the Chinese carmaking capital of Changchun, where USA Today sent me to chase down Yao at the Chinese Basketball Association's All-Star Game. It was on this assignment that I realized I could be really good at both freelancing about even topics I'm not naturally knowledgeable about and parachuting into foreign lands and finding the news.

In January, I had attended a CBA basketball game in Beijing for two reasons. First, I was curious what it would be like and, secondly, the very first morning after I arrived in Beijing I looked out my 13th-floor apartment window to see the words "NBA" and "I Love Basketball" written in English in the snow on a basketball court. I had gone to China to kick back, take stock and NOT work -- sounds familiar now, doesn't that? -- but great stories slapped me in the face everywhere I turned, the Chinese hankering for hoops being the very first. I soon learned that the Chinese were mad for American basketball and that Chinese TV aired one live NBA game every day overlaid by their own color commentary in Mandarin.

Here's how I described the game in a weekly e-mail missive I'd send to my friends and family from China in the era before blogs:

We found a thumping, pulsating arena -- site of 2008 Olympic badminton, perhaps? -- where we were lucky to get seats together and many fans happily stood in the aisles and along the railings to cheer as the team played beneath a massive Chinese flag. Scalpers lurked outside, a guy in a duck suit roamed the room as Beijing's mascot and the loudspeakers blared Ricky Martin and the Backstreet Boys as a dozen cheerleaders in black tights and shimmering butterfly vests danced about the court during time-outs. I noted there seemed to be few families in the audience, but then realized that under China's One Child policy, there aren't as many children so you're not going to bump into a the irksome broods that make outings at professional sports in America so much fun.

It didn't take long for me to learn about the Chinese stars who wanted to come to the U.S. and the NBA's desperate desire to expand and exploit this mammoth new market. In fact, that basketball game was the first time I saw any non-tourist black people in China; they were NBA rejects. Each Chinese team was allowed to hire two foreign players.

It seems obvious now that the U.S. was about to have a Chinese NBA invasion, but Americans had not heard much of a peep about this when I landed. Sports Illustrated had written something about Yao and another Chinese player named Wang Zhizhi, but they hadn't interviewed them and their story was at least two years old.

Timing and drama conspired in my favor. The Chinese didn't want Yao to come to the U.S. yet because his team, the Shanghai Sharks, hoped he'd help them win their first national title first. Also, Chinese culture demanded that the older, 23-year-old Wang go first, and Yao couldn't enter the NBA draft on his own anyway at that point because he was under 21. In the end, Wang came that year, and this was how I wrote about his entry into the draft on

the front of USA Today's sports section in March 2001:

BEIJING -- He's a basketball player, so he's supposed to be tall.

But when 7-foot Wang Zhizhi strides through a Beijing restaurant en route to a private karaoke lounge to conduct an interview, it's hard not to be stunned by how close his head comes to the ceiling.

The Chinese gape because Wang, 23, is one of the most famous basketball players in China. American tourists stare, too, wondering who the giant might be.

They'll likely find out soon enough. Wang is in the final stages of securing a release from the top military basketball team in China to sign with the Dallas Mavericks, which could occur as early as Thursday. He's likely to be followed this year or next by 7-6 center Yao Ming, 20, as the first two Asian players in the NBA.

After that, though, I kept hearing how openly displeased Yao was with his forced deferral, and I convinced my editors at USA Today to let me track him down in Changchun. I don't even remember how I did it; I worked a circuit of translators and NBA sources but I swear there was also a little hotel camping-out involved.

What I got was

this:CHANGCHUN, China — Yao Ming doesn't want to be here anymore.

The potential No. 1 pick in this year's NBA draft isn't interested in putting on slam-dunk performances for the Chinese masses at their All-Star Game here. He absolutely loathes having to sit for questions from the Western media about his future. And he cringes at the growing likelihood that he may be forced to skip this year's draft to stay in China another year or two and continue to play for the Shanghai Sharks.

The mind of this anxious 20-year-old with almost no say in his own destiny is an ocean way, in a land where scouts are buzzing about his vast potential and where his compatriot, Wang Zhizhi, suited up Thursday night as a Dallas Maverick. Yao says he wants to enter the draft this year if he is permitted to make himself eligible, which he called "almost a sure thing."

This was an important piece for a few reasons. First, it was a thorough introduction of this monumental figure to the United States audience on page 1A of the largest-circulation newspaper in the nation. And second, it actually showed Westerners that Chinese people can, under very specific circumstances, get away with criticizing the government and official decisions. This circumstance was that this was an extraordinarily gifted athlete and potential cash cow, not a grunt. Later, the Chinese authorities would confiscate a fairly sizeable chunk of his NBA earnings.

Here was the money line from Yao, who spoke through an interpreter because he was years away from speaking English:

"I appreciate the CBA and I am happy playing here. But now I am ready. I want to be with the best."

The next year, after Wang broke us in over here, he got his wish. He was drafted No. 1, and I covered the

machinations of that, too. After that, the story was the province of sports writers, not folks like me more interested in the geopolitical and fiscal implications than on-court action.

Years later, a university student in America contacted me. He was doing a piece on people faking photos on the Internet. He was sure the shot above was bogus. I assure him -- and you -- it was not. It was an awesome moment in time.

1 comments:

Omg, you look so young!

Post a Comment